|

Macintosh-based computer graphics designed and executed by Red Dot Interactive of San Francisco

were used to illustrate two math problems, Chebyshev's theorem and a presentation of Ramsey

theory. Ramsey theory as expressed in the "party" problem shows how quickly a simple problem

grows in complexity to a point where there is no solution in sight, either by computer or

mathematical proof. The problem's presentation in two forms (one by Erdős, the other with

animation) makes it accessible to non-mathematicians, and provides an example of how a

mathematical proof can make exhaustive calculations unnecessary.

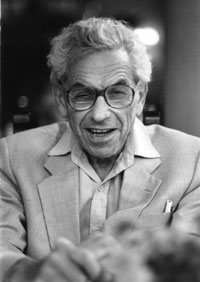

Despite his intensely social working style, Erdős was a man who never married or settled down.

Ultimately, we see him alone, and as Michal Karonski, a Polish mathematician, says,

"perhaps very lonely." Whenever Erdős encounters a child, be it in Muir Woods, California

or on a Budapest playground, he performs a trick, but the trick merely baffles the child and

shows Erdős's innocent awkwardness in social situations. In a deeply personal moment Erdős

confesses that he never married because he could never stand sexual pleasure-a trait he

believes to be a unique abnormality. Despite his intensely social working style, Erdős was a man who never married or settled down.

Ultimately, we see him alone, and as Michal Karonski, a Polish mathematician, says,

"perhaps very lonely." Whenever Erdős encounters a child, be it in Muir Woods, California

or on a Budapest playground, he performs a trick, but the trick merely baffles the child and

shows Erdős's innocent awkwardness in social situations. In a deeply personal moment Erdős

confesses that he never married because he could never stand sexual pleasure-a trait he

believes to be a unique abnormality.

The most important relationship in Erdős's life was with his mother. A powerful woman who

nurtured his interest in math, Ana Erdős took care of her son and traveled with him well into

her nineties. She became overly protective of her son after losing her only other children

(two daughters) to scarlet fever a few days before Erdős was born. The mutual love and

dedication between Erdős and his mother are described in some of the most emotional scenes

in the film. The loss of his mother defined his loneliness to the end of his life. Hungarian

mathematician Vera Sós explains that after his mother's death, Erdős refused to stay in the

Budapest apartment where she lived and would not even enter it alone.

Mrs. Anne Davenport and Lady Jeffreys, both widows of English scientists and close friends

of Erdős since his days at Cambridge in the 1930s, punctuate the film with their comments on

Erdős's often childlike naiveté and innocence. Indeed, we see him boarding planes in Budapest

and San Francisco, wandering the streets of Budapest, pacing in the library at Princeton's

Institute for Advanced Study, and walking across a Cambridge lawn-with the same distinctive,

lost look, his mind locked on a math problem.

At a Poznan banquet in his honor, Erdős imparts his favorite stories about how other famous

mathematicians died. When George Pólya was 97, Erdős toasted him and promised to celebrate his

100th birthday with great splendor. Pólya said, "Maybe I want to be 100, but not 101, because

old age and stupidity are too unpleasant." Pólya died when he was 98. Erdős sits down, then

remembers another story about the great mathematician Leonhard Euler (1707-1783). When he died,

Euler just said, "I am finished," and collapsed and died. When Erdős once related that story,

he says, another mathematician "callously remarked, 'Well, another conjecture of Euler's has

been proven.'"

In an age when genius is a mere commodity, it is useful to look at a person who led a rich

life without the traditional trappings of success. True dedication to a life of the mind has

its own rewards, as Joel Spencer eloquently explains in his concluding remarks on the quest

to unveil new pages of "The Book." At the end, Erdős is alone in a guest room, reading and

writing in the notebooks he kept all his life.

|